Approved Literature

| This article or section is being fought over by people undoing each other's changes. Please use the Discussion page for fighting instead of the article. |

This page lists the genre fiction which is popular on /tg/, along with a brief description and the notable areas of merit. See below for a brief rule on thumb on relevance.

The Jane Austen principle[edit]

Jane Austen's work has been a staple of English Literature for two centuries. It's been adapted for stage, screen and television and beloved by millions. That said, while "Pride and Prejudice" might be a timeless romance that can move the heart, it is pretty far removed from the shared interest of the sort of people which might come here (at least until someone whips up a really good Dice and Graph version). This is not a knock against Jane, her work or you for liking it or some other removed work of literature, just a fact to keep in mind when adding things to this page.

TL;DR Good material is not automatically relevant to 1d4chan and /tg/.

Fantasy[edit]

- Richard Adams - Watership Down: The epic story of a tiny band of desperate people's odyssey to flee a great calamity and find a new homeland. Along the way, they fight dangerous battles, encounter dangerously seductive dystopia after dystopia, and ultimately destroy a fascist dictator before founding a new nation. Also, everyone's a rabbit. Badass storytelling, sweet worldbuilding, and an incredible level of quality for a children's book.

- R. Scott Bakker - The Prince of Nothing: The series is set in the world of Earwa, based on Hellenistic Greece, Scythia and the Byzantine Empire, where a descendant of an ancient emperor - Anasurimbor Kellhus ventures forth with preternatural skills of prediction and persuasion derived from advanced knowledge of psychology and mental biases to conquer a world wracked by rival wizard schools, imminent holy war and ancient inhuman races vying to bring forth a second apocalypse. The series also deals with various metaphysical and philosophical issues stemming from the setting and it's elements.

- L. Frank Baum - The Wizard of Oz: Dorothy and her little dog too get isekai'ed, meet companions, defeat the witch. Baum (or rather, his publishers) milked this franchise to death releasing sequel after sequel, so stick only to the first book, unless you're doing weird idea mining.

- Terry Brooks - Magic Kingdom of Landover: A book series about a Chicago lawyer who discovers an unusual offer in a mailing catalogue: the sale of a magical kingdom. He quickly finds out that not only is the offer real, but just because he bought a kingdom doesn't mean its inhabitants are too eager to accept him as their new king. Lots of crazy, humorous adventures follow. What the series does best is being a pretense-free fantasy comedy, that doesn't try to reinvent the wheel, deconstruct anything or flex with extensive worldbuilding. One of the main inspirations for Majesty, while itself looking at Wizard of Oz and taking notes.

- Jim Butcher - The Dresden Files: Basically the World of Darkness with

allmost of the depression, brooding, doom and gloom replaced with badass, humour and a pinch of noir detective. Follow the young wizard/private investigator Harry Dresden through his misadventures in a supernatural world of Chicago, as he grows in power and fame, deals with ever increasing levels of supernatural horrors, get his life ruined to oblivion and beyond and yet manage to make it look cool rather then utterly depressing and sanity-check inducing by sheer will alone (OK, will and snarkiness).

- Brandon Carbaugh - Deep Sounding: A two-part story written by a fa/tg/uy, dealing with themes of isolation in a Dwarven society. Consistently humorous and socially relevant.

- Glen Cook - The Black Company: I can't remember the exact quote, but someone put it best when he said "it's a story about level 5-8 badasses trying to make it in a world dominated by epic level Wizards". Follow the mercenary entourage known as the Black Company as they sell their swords to the highest contractors, who usually end up being The Big Bad Evils. The first three books (now conveniently available as one book, "Chronicles of the Black Company") are good then things start to get weird.

- Larry Correia - Monster Hunter International: In the modern world monsters of all kinds are out there. Stopping them from eating humanity are private groups of monster hunters who get paid very handsomely for removing the supernatural with superior firepower. As one would expect from an author with a background in running a gun store and competitive shooting, it's very /k/. A character's choice of firearm describes them as much as their clothes or hair and guns work as they're supposed to. The first book (which can be obtained as a free e-book) is enjoyable, but very rough, and the series improved dramatically each book. Features a writing style that improves dramatically when listened to as an audiobook.

- Grimnoir Chronicles: A separate series by the same author. Set in an alternate 1930s where a small (but constantly increasing) percentage of humanity has been born with super powers since at least the 1830s. While there's X-men style discrimination, it's largely in the background. The series is actually about how Japan is trying to use its research of Power to take over the world. The super power system is unique in that there are only about 30 documented Power types, with many just being lesser versions of other powers, and outside of a core handful everything else is rare but the creative and powerful can stretch the rules. The world has also had cultural and technological shifts as a result of Power instead of keeping it the same aside from their existence.

- Steven R. Donaldson - Thomas Covenant: The first two series are the ones /tg/ has read - there's a (much) more recent series that ostensibly wraps it all up, plus some outtakes (like "Gilden-Fire") that SRD refactored as shortstories. The titular character nuzzled the wrong armadillo apparently so is a leper. In the story he gets isekai'ed; driven with self-hatred and a refusal to compromise, he does horrible things but anyway has to defeat the BBEG named, we shit you not, "Lord Foul". Massive influence on Monte Cook's Arcana Unearthed oeuvre (particularly) so we gotta note it. The Ansible #46 article "Well-Tempered Plot Device" hilariously described these two series as "so flatulent you have to be careful not to squeeze it in a public place"; publisher Lester Del Rey is rumoured (Ansible #50) to have disliked the series too, but (correctly) judged the (mid 1970s) moment as good to release some fantasy any fantasy. SRD wrote some other fantasy and SF; only fans of the Covenant books went on to buy those, but they number enough to maintain Donaldson's alimony payments. Characters get forcibly boned in those stories too.

- Steven Erikson - Malazan Book of the Fallen: An enormous read that stretches across over three million words and ten books, Erikson's worldbuilding rivals anybody else in the genre, with a large focus on the many different cultures, how they rose, and then how they fell. Can be overwhelming at times due to the sheer number of simultaneous plotlines and a large, perhaps even bloated, cast. Very much the definition of epic fantasy, the level of power at play swings fairly wildly depending on which set of characters is being focused on at the time, from assassins fighting upon rooftops, to flying castles being crashed into cities, and then back to the oft-humorous exploits of a group of mostly mundane soldiers that is reminiscent of Glen Cook's Black Company. In all, a story full of engaging personalities exploring a supremely fantastical world, with all the hallmarks of classic fantasy, elves, dragons, gods, and wizards, given a unique spin.

- Raymond E. Feist - The Riftwar Cycle: A 30 book epic written over the course of three decades, The Riftwar Cycle starts off as the story of a boy learning how to be a wizard, only to save the world by the end of the debut novel, Magician. After this the series evolves into an epic spanning multiple generations of characters (but roughly half focusses on the initial cast) fighting to protect their world from internal political strife and malevolent external forces. Grew to be a lot more cosmic in scale in the last eight or so books, and the ending was kind of a lacklustre business. The classical fantasy races are not the focus here: the dwarves and elves get along just fine, and while there's dragons, serpent folk and dark elves (the latter of whom are Native American inspired), it's mostly about humans and their struggles. The series is divided into ten sagas, with the best one being the Empire trilogy which tells the tale of the chronologically six first book from the perspective of the antagonists in a beautiful tale of loyalty, honour, politics and love. Was also Neal Hallford's inspiration for Betrayal at Krondor, a Dynamix / Sierra vidja that is held in high esteem in some circles. Not enough circles, apparently; since Hallford's remaster proposal didn't get funded.

- Neil Gaiman - American Gods, The Graveyard Book, Neverwhere, Sandman, etc.: An entertaining and occasionally preachy writer, he's known for his unique and well fleshed out ideas. There's something here for everyone, from the Noblebright Stardust to the fairly grim and pretty dark Sandman comics. American Gods, however, is the one he's best remembered by, which is a story about physical manifestations of IRL gods fighting a losing war against globalization, mass media and technology. There's also a part where a man is swallowed whole by a woman's vagina.

- Jane Gaskell - The Atlan Saga: A series of gloriously cheesy fantasy novels from the 60s that combine all the best elements of pulp with post-modernism. The misadventures of a heiress to Atlantis empire in the prehistoric world where various myths - and genre cliches - are all true. It's the last big thing in the genre that didn't try to copy-cat Lord of the Rings, so worth reading for originality alone, along with being what shaped various cliches regarding Atlantis ever since.

- William Goldman - The Princess Bride: The book the famous movie was based on. Has a couple of twists and details left out of the movie, usually for good reasons. Still worth reading, though.

- Michael John Harrison - Viriconium: A truly peculiar set of novels and short stories dedicated to put traditional world building on its head, by never making sure if the stories are happening between the same characters, in the same place or same time. A very open-ended to interpretation "setting", which is also a great exercise to how tell a story without overburdening anyone with details and in the same time providing all the important elements to keep audience (readers or players) invested and interested.

- Robin Hobb - The Farseer Trilogy and The Liveship Traders: First is a story of a royal bastard's horrible upbringing as an assassin. Second is a story of magical sailing ships that talk, dragons, pirates, rape, 14 year old girl overcoming terrible misfortune. It has it all. (Please note the following two sets of books in the series are a little average compared to these two). The endings of the books in the second series are a little pat, but are still entertaining.

- Robert E. Howard - Conan the Barbarian: Conan the Barbarian was born from this quill. A seminal pulp classic which could be considered the father of sword and sorcery.

- N. K. Jemisin - The Broken Earth Trilogy: A post apocalyptic trilogy with a heavy spiritual and existential emphasis in a post-humanist story.

- Ursula K LeGuin - Earthsea Cycle+: Threads about /tg/-approved literature will consistently end up having a poster say something to the effect of "no Sea Jedi Wizard Chronicles WTF" about halfway down, immediately being followed by a chorus of agreement. Needless to say, this series is an excellent one, little-known but surprisingly influential. It's the series that established the concepts of the concept of nominal magic as understood in modern fantasy literature: names of power in the language of magic are spoken to exert power over the person, place, thing or idea that name refers to. Later, less-respectable novels such as those by Christopher Paolini would abuse this concept for fun and profit. Sadly, such novels seldom strive to equal the actual accomplishments of the Earthsea novels, such as the successful building and display of a rich, believable, and internally consistent setting without letting any of the world building bog down the narrative like in LotR.

- Fritz Leiber - Swords and Deviltry, et al.: A runaway momma's boy and a failed magician's apprentice lose everything and become thieves in Lankhmar, centre of civilization and debauchery. They are Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser:, swordsmen supreme, insatiable adventurers, womanizers unequalled, and bros of the highest calibre. Together, they plunder the world of riches, bitches, and wine, while facing magic and horror of a decidedly cosmic sort.

- C.S. Lewis - The Chronicles of Narnia: Oxford don retells the Johannine Passion, but in Oz-expy Narnia with literal Jesus-lion Aslan. Our man is inferior (even) to Baum as a worldbuilder, but very good as characterbuilder - particularly for Edmund, Lucy, and (later) Eustace. Ends with an apocalypse and visitors going to Heaven too. Except older sister Susan, who no longer wanted to go as she'd wrote off her time in Narnia as fairytales.

- Charles De Lint - Someplace to be Flying and Trader, Pretty much all of his books, you can't really miss: Most of the books seem to be set in Canada and revolve around Gypsy folklore and Native American spiritual stuff with urban settings. Don't get attached to characters.

- George R. R. Martin - A Song of Ice and Fire: Some of the better character development in genre, with a bit of mystery, political chess and high death rate. Tends to drag at times, and since the release of the HBO series will be consistently overrated by those who've seen little else. Final books' publication is so delayed, they may or may not be finished before GRRM's death. Noted for Tolkien-envy.

- Matter of Britain - aka Arthurian Literature. This covers a very wide set of stories, but the most commonly accepted and cited books include Le Morte D'Arthur by Thomas Malory, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight by Anonymous, the Lancelot-Grail cycle, and many more. Even if you're already familiar with the general outline of Arthurian lore, going back to the sources - particularly at different time periods - provides a new perspective on medieval literature and how differently the stories can play out across different authors, creating a mosaic of Celtic mythology, French chivalry tales and even self-reflection on knighthood.

- Michael Moorcock - Elric series (and so many others) An iconic author, albeit considering the number of books he has written, very hit and miss. Elric is his most popular character. Stick to the collected sets Stealer of Souls or Stormbringer as a starting point though. Remember that Elric is first and foremost an icon for heavy metal, so adjust your expectations accordingly.

- Terry Pratchett - Discworld series: Starts from parodying Fantasy as a genre, soon turns to far beyond AWESOME, starting when Death himself seeks an apprentice. One of the most successful fantasy novel series in recent history. Rare combination of good humor and wise messages. Does get a little preachy towards the end, but hey, it's still a great read.

- Phillip Pullman - His Dark Materials: In another world in which people's souls manifest outside their body as animals and Polar Bears are sapient, a girl gets caught up in intrigue involving the Powers That Be in an adventure across dimensions.

- Patrick Rothfuss - The Name of the Wind: A mary sue bard goes on mary sue adventures (arguably an unreliable narrator) - world building may be weak but it's a fun read, so enough people on /tg/ have read it to count, even though nobody will praise it.

- Emily Rodda - Deltora Quest: A gargantuan project written to pay bills, under the guise of a children-oriented book series that tell the overarching tale of a band of heroes in the magical world of Deltora. It is divided into three quintologies: "Deltora Quest" (the by-the-numbers generic heroic fantasy), "Shadowlands" (the by-the-numbers turning of the tide against forces of evil) and "Dragons of Deltora" (the by-the-numbers "dragons aren't really extinct" saga). Aside those, there are also: three lorebooks that expand on the Deltora world, and two sequel series set in the same universe (The Three Doors and Star of Deltora). The main sell isn't the generic writing and plots, but the extensive worldbuilding that goes along with it and stays roughly consistent. If anything, a good mine for monsters. Also had a decent anime adaption.

- J.K. Rowling - Harry Potter: Love it or hate it (and there are things to hate,

especially where the author herself is concerned...which is, at best, an irrelevant point to mention here as differing opinions between writer and reader have NO effect the quality of their work in the slightest...a fact people sadly tend to often forget) this series is a big part of the collective fantasy consciousness, especially where normies are concerned. As such, if you want a tone that is easily familiar to those unfamiliar with fantasy in general, or children, this is not a bad place to start. At best, they're pretty readable books; at worst, they're thoroughly mediocre and derivative as all hell. At the very least, you'll look less of a neckbeard knowing what a Muggle is. MAIN BOOKS ONLY.

- Andrzej Sapkowski - The Witcher (especially the short stories): While the Witcher saga is just getting more bland and increasingly more generic with each following part, the two initial books collecting all the short stories (especially "Sword of Destiny") are the reason why everyone treated Witcher as unique and original. Tonnes of wacky ideas how to spin cliches and old tropes into something fresh. Reading the saga proper is not required and generally not advised, especially with wooden English translation.

- Alternatively, the later saga can be read for precisely what it is routinely bashed for. Starting from "Baptism of Fire", it turns into an unapologetic "you all met in the forest reserve and your party is tasked with retrieving a lost princess" campaign. If read with such mindset, it's pretty good after-campaign report, including random hijinks, new players joining half-way through and bunch of party in-jokes about the situation at hand.

- J.R.R. Tolkien - The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and anything else he wrote (eg; the Silmarillion): The great grand-daddy of modern fantasy. Not having even the slightest familiarity with his work is inexcusable in eyes of /tg/.

- Karl Edward Wagner - Kane series: Essentially a more grimdark version of Howard's style of sword and sorcery, Kane is more akin to a villain that Conan would fight than the "noble savage" barbarian archetype. Immortal and cursed with the inability to ever truly settle down, Kane is an expert fighter, leader of men and potent sorcerer. After thousands of years his only real goal is to stave off boredom, which he does by offering his services and considerable intellect to various rulers, although more often than not with an ulterior motive. In one story he sets out to revive a race of ancient cosmic horrors simply because they offered him a chance to explore the cosmos.

- Gene Wolfe - The Book of the New Sun: The setting is inspired by Jack Vance's Dying Earth series (itself lifting from Clark Ashton Smith), so this could be either in SF or Fantasy. A torturer is exiled from his guild and old life after he helps kill the woman he loves to spare her from the agony of torture, now forced to journey through Urth; our Earth in the far, far, far future, in a time when our sun is beginning to die. These books do not make for easy reading, however. The author uses lots of very obscure words to create the worlds own unique lingo. Also, the main character is an unreliable narrator of the more extreme sort. The reader will be spending some time figuring out what are the truths and what are the lies.

- Roger Zelazny - The Chronicles of Amber: A lesser known series (although it's in Appendix N too) written between 1970 and 1991 about a family of (essentially) demigods who inhabit the "true" reality of the city of Amber. Everything else is merely a shadow of Amber and its inhabitants. The princes and princesses can move freely between Amber and an infinite number shadow worlds but the constant plotting and backstabbing at home and the less-than-real nature of everything outside makes them callous and often amoral. The first book effortlessly turns from "hard boiled detective story" to "psychedelic road trip" to "drama about Greek gods" in style.

Science Fiction[edit]

- Douglas Adams - The Increasingly Inaccurately Named Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Trilogy: One of the funniest works of science fiction ever made, although you could count it as the first. The precursor to all comedy stories about everyday people having to deal with the absurdly massive and meaningless universe around them. Grab your towel, make a fresh cuppa, and make sure you've got enough tape to keep your sides from splitting too much.

- K.A. Applegate - Animorphs: Mighty Morphin Power Rangers: The Furfag Edition. A group of teens with attitude accidentally gain power of "Morphing" into various creatures of their choice and then get almost instantly tangled into guerilla warfare against an alien invasion. If you're an Anglophone furfag, there is a good chance this series has something to do with it. On the flip-side, the series is fucking dark, playing up the situation for as much horror and misery as it can get away with... which is pretty impressive for something that can be summed up as "sci-fi Dungeons & Dragons all-druid party vs. body-snatching alien invasion for twelve year olds!" It also had a 1990's Nickelodeon live-action show. The books are also a great source of alien creatures, like the ever-hungry Taxxon centipedes whose design and schtick of endless hunger were stolen for the hostile xenos of the videogame Starsand.

- Neal Asher - The Gridlinked Series: Some of the best, hardest sci-fi out there, this is one of those universes that has unique, creative technologies (rare nowadays)as well as 007...EEEN SPESSS

- Isaac Asimov - Foundation Series: The seminal space opera modelled roughly on the decline of the Roman Empire, includes everything from primitives and feudalists too ignorant to work what technology remains to Space Capitalists looking to exploit said primitives with subscription plans. It follows the rise of a new civilization from this empire's decline and eventual death, as well as the danger of relying too much on great plans laid centuries before by a single man. Focus more on the political transformation than the science behind it. The very model of Empire-In-Decline SF, and very useful material for GMs looking to explore settings outside the usual space-empire backdrop.

- Paolo Bacigalupi - Pump Six and Other Stories: Biopunk meet post-apo and hefty dose of shady business. Think Shadowrun, minus the magic.

- Iain M. Banks - The Culture Series: A series about a perfect, utopian spacefaring society and all its many problems. Some of the grandest-scale worldbuilding in science fiction, and full of clever ethical and political musing.

- Stephen Baxter - The Xeelee Sequence: For those for whom Donaldson just isn't rapey enough, Baxter is here to scratch that itch. Backdrop is the cosmic war between the Xeelee and the dark-matter entities "Photino Birds". Starts with The Ring. Baxter wrote a lot of other crap too, like Proxima and Stone Spring/Bronze Summer; likewise full of nasty. We'd rather not discuss this stuff either but Xeelee has its fans on /tg/: this entry is dedicated to you, as long as you read it outside a 500 yard radius from a school.

- David Brin - The Postman: First novel to present post apocalypse not from the point of view of badass heroes or insane raiders, but random villagers and such. Great world building for a very small world. Has infamous film "adaptation", sharing only title.

- Edgar Rice Burroughs - the Barsoom Series-aka Mars Chronicles and the Pellucidar Series: Iconic, manly, and fuckin' A! This guy also did Tarzan and a whole slew of other works that would go on to inspire other manly stories, chiefly Conan the Barbarian and most of the knockoffs thereof.

- Glen Cook - The Dragon Never Sleeps: Basically an EVE Online novel written decades before EVE Online. Was supposed to be a trilogy but the publisher wouldn't okay sequels so it gets rushed at the end. Not as iconic as The Black Company, but this one has LATE ROMAN EMPIRE IN SPAAAAAAACCCCEEEE!!!!!!!

- James S. A. Corey - The Expanse series Bar the intentionally fantastical elements it provides

a fairly groundedmuh gritty realism version of near future space exploration. Some fantastic characters and stories, but as the main plot goes, slowly turns into a generic space opera-western mix. Got an unapproved TV show adaptation that ignores all the good stuff, while taking the worst aspects of the books and runs wild with them.

- Arthur Conan Doyle - The Lost World: The other thing Doyle is know after Sherlock Holmes. An archetypical novel about bold scientists, ambitious hunter and intrepid reporter going into a distant plateau somewhere in the Amazons, where they have all sorts of misadventures involving species that should be extinct millions years ago - and most notably living dinosaurs. There is a good chance you "know" this book, along with all its plot bits, without ever actually reading it, that's how big and influential it is.

- Harlan Ellison - I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream: The last five humans alive are being held deep in an underground complex, where they are perpetually tortured by AM, the sadistic AI that wiped out the rest of humanity, with no hope of escape. The most creepy thing in this book is that the author thought it was optimistic. If he someday went to write something pessimistic, the universe would implode from the sheer grimdark overdose. The sequel of it, in form of a point-and-click adventure game, is also very much approved.

- Philip Jose Farmer - The Riverworld Series: A group of dead people from many different time periods, including Richard Burton, Hermann Göring, Tullus of Rome and Mark Twain wake up on an alien planet and have to survive. Very fun read with interesting character interactions.

- Robert A. Heinlein - Starship Troopers: Where Space Marines and Tyranids came from. The novel carries a vastly different message and tone than the campy movie based on it. Roboute Guilliman keeps a copy in his duffel.

- Frank Herbert - Dune & its earlier sequels: World-building, politics, super-humans - it's one helluva party. The spice must flow!

Navigators are totally not stolen from Dune*BLAM*.

- Aldous Huxley - Brave New World: Take 1984, and do the total opposite the way people are controlled (rather than punishing bad behavior, it's rewarding good behavior) mixed with a Tau-esque genetically enforced caste system and conditioning to make people embrace their servitude.

- William Gibson - The Sprawl Trilogy: Neuromancer is the start of Cyberpunk. Gibsons short stories and the sprawl trilogy basically invented the whole genre and had a massive influence on internet culture before the internet even existed properly. The Matrix movies ripped off huge chunks of the sprawl trilogy, and Gisbon invented most of the basic internet slang (Cyberspace and Netsurfing in particular). All cyberpunk RPGs and Vidyas want to be Neuromancer.

- William Gibson - The Difference Engine: A thought exercise that went along the lines of "what if cyberpunk, but in a different time period?". Henceforth - steampunk. Don't panic yet - this one comes with the actual punk in it, rather than cogs and brass glued to things. For what it's worth, it's reskinned Neuromancer and a great example of why steampunk is but an aesthetic, rather than a genre.

- Wolfgang Jeschke - The last day of Creation: Having figured out that time travel is not only feasible, but already was done by someone, the US government decides to send supplies and engineers to the past with a sinister goal - siphon the oil from the Middle East and pump it to more "friendly" territories, with utter disregard if the plan is even feasible. A whole lot of things go wrong, and the fact people from countless alternative futures keep barging into the past is the least of the problems. Was "adopted" into approved vidya, Original War.

- Stanisław Lem - Tales Of Pirx the Pilot: Collection of short stories documenting gradual progress of humanity in space exploration and AI development. Nice deconstruction of all the shitty elements from space opera, before there even was space opera.

- Andri Magnason - LoveStar: Equal parts biting satire and bittersweet love story, set in a bizarre future (think equal part of Brave New World, corporate dystopia and high-concept sci-fi). It's the humour and creative application of own setting and its rules that makes it helpful for worldbuilding that amounts to anything more than just trivia.

- Walter M. Miller, Jr. - A Canticle for Leibowitz In the grim darkness of the far future there is only Catholicism. Think Fallout meets Catholic Church and you wouldn't be too far off.

- Larry Niven - Ringworld (and more broadly Known Space): Many, many stories are set in this future setting. Features FtL travel, several alien races living and dead, and deep lore from the far past. There's a war with catgirls called Kzinti, which events Niven has let other authors write. The Ringworld is a Dyson sphere on the cheap: instead of wrapping the entire sun, "only" the inhabitable orbital ring is built up, above the stellar rotational equator.

- George Orwell - 1984, Animal Farm: WAR IS PEACE, FREEDOM IS SLAVERY, IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH! FOUR LEGS GOOD! TWO LEGS

BADBETTER!

- Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson - The Illuminatus! Trilogy: /x/ the book, and a cult classic in every sense of the word. Once you get used to the massively cheesy tone, what you'll find here is an intelligent and fun series of books that are both a parody and a send up to: 70s counterculture, Western esotericism, political and religious dogma, numerology, and conspiracy theories.

- Robert Sheckley - short stories: once dubbed the clown prince of sci-fi, recommended by Douglas Adams.

- John Steakley - Armor: Future soldiers in powered armour fighting against insectoid, always hungry aliens and suffering from mental trauma and PTSD... man, that does sound familiar.

- Charles Stross - Missile Gap: While Stross is most famous for his Laundry Files (basically collection of Delta Green shorts, which are all worth reading too, and eventually even got their own TTRPG), Missile Gap is just mind-numbing novella about entire Earth being transported on an Alderson disk... or maybe a snapshot of Earth... or maybe both. All right in the middle of the Cuban Crisis. Think "Primer" meet Tom Clancy techno-thriller.

- Jules Verne - Journey to the Center of the Earth: While Verne penned a trainload of sci-fi and adventure novels, this one is the closest to a TTRPG format: a small expedition of daring adventurers goes under the surface of the Earth, to prove the Hollow Earth theory, facing various dangers and monstrous creatures. Quarter of references Hollow Earth Expedition RPG makes is to this book, for obvious reasons.

- Andy Weir - The Martian: An astronaut left on Mars has to survive until he's rescued. Decent inspiration if you want to make "NASA exploring distant worlds" as a campaign setting, but if you don't like loads of technical details this might not be the book for you.

- H.G. Wells - The War of the Worlds and Time Machine: Absolute classics. Not knowing them is akin to being illiterate, while they can be used for all sorts of games.

Horror[edit]

- John W. Campbell - Who Goes There?: Remember John Carpenter's The Thing? Well this is where it all started. Taking into account when the novella was written is the real game-changer.

- Laurell K. Hamilton - Guilty Pleasures: Probably one of the most iconic and influential urban fantasy in existence, despite seemingly obvious setup for occult detective. While the rest of the Anita Blake series is unquestionably in shunned territory, this one is still a must-read. Also, mind the title.

- Aneta Jadowska - Dora Wilk series: Essentially Anita Blake: Polish Edition. Unlike original, doesn't turn into BDSM harem porn, but instead gradually distances itself from romance and focuses on the world-building and occult. Also, it fully embraces being written to cover for bills. Decent fan translations exist.

- H.P. Lovecraft - At the Mountains of Madness and anything else published after it: Lovecraft is to modern horror what Tolkien is to fantasy. While his early stories are mediocre, starting with At the Mountains of Madness, their quality rises sharply, explaining how this guy reached such memetic status.

- Richard Matheson - I Am Legend: Single-handedly responsible for creation of post apocalypse genre and modern take on zombies and vampires. Also, depressive as fuck, so bring some tissues. No, really. None of the 3 film adaptations managed to match the quality of the novel.

- Anne Rice - The Vampire Chronicles: Where Vampire: The Masquerade started. You are probably already familiar with this particular style of vampires even without knowing there were any books, that's how iconic the imaginary is. And for the sake of everyone's sanity, let's just pretend the Chronicles consists of only three books: Interview with the Vampire, The Vampire Lestat and The Queen of the Damned. You really don't want to read any further titles, trust us on that, especially since this is a self-contained trilogy.

Adventure[edit]

- Michael Crichton - Congo: A modern day expedition in search of a diamond field in the Congolese uplands ends up finding far more than they bargained for: the remains of a lost civilisation and the local cryptids ready to kill anyone entering their territory. This being a Crichton novel, you can expect playing with genre conventions and transporting "classic" plot devices into modern setting, which has twofer benefit: you get it distilled to its purest form and also taking into account modern tech.

- Clive Cussler - Dirk Pitt series: Take Indiana Jones, add half of MacGyver and few splashes of Ethan Hunt. Stirr together, serve ice-cold and seasoned with Rambo camouflage. While the quality of the series warries wildly from book to book, this is the closest thing to a modern pulp, with larger-than-live characters and their crazy, globetrotting adventures in search for treasures and the thrill it brings.

- Henry Rider Haggard - King Solomon's Mines: Grand-daddy of the adventure fiction as understood today. You already know the basic premise and general plot without even reading it, that's how many times it was adopted and how many genre conventions it set in stone. Other Haggard books are also approved, even if far less famous nowdays.

Alternate History[edit]

- Poul Anderson - Time Patrol: A collection of stories about the titular Patrol - a policing body overseeing the time stream itself, and correcting all the alternations done by third parties. Which due to the way how the universe operates in-story requires routinely wiping out entire new timelines from existence. There is at least a single Alt!Earth present per story and sometimes the alternations persist even after being "fixed". Absolute classic, responsible easily for inventing half of all time-travel and alt-hist plot devices and cliches.

- L. Sprague de Camp - Lest Darkness Fall: Martin Padway, a mild-mannered historian, gets hit by a lighting in 1939 and wakes up in Italy, 535 AD, right before Gothic Wars will unfold, destroying the region entirely and leaving Byzantine Empire in ruin, starting Dark Ages for good. Armed with the knowledge of the following events, along with a bit of dramatic flair, Padways decides to prevent that, irrevocably altering the history to one where the "darkness never fall". The book is most notable for giving justice to all the barbarian tribes living in the remains of Western Roman Empire, portraying them with a lot more nuance than "horde of caveman squatting in ruins" and avoiding most of Romanaboo bullshit.

- S. M. Stirling - The Apotheosis of Martin Padway: A sequel of the above, more in line with "proper" alternative history, set 50 years later and examining the logical conclusions of all the changes caused by Padway, both in Italy, the Med Basin and world at large. If you ever wanted (very) late antiquity setting, but weirder and far more sophisticated with its culture and tech, look no further.

- Naomi Novik - Temeraire Series: Basically "Horatio Hornblower, but with Dragons". It's the Napoleonic War and a Royal Navy captain finds himself unexpectedly bonded to a Dragon Hatchling.

- S. M. Stirling - The Peshawar Lancers: In the 1878 a bunch of comets hit the Earth causing much havoc and forcing the British to evacuate to warmer parts of the world. In 2025 the British Empire still reigns as the most powerful nation on Earth run from Delhi, along with French Africa, the Japanese Empire and a rather nasty Russian Empire in a world powered by steam. If you want steampunk that's more than superficial, exotic and just all around well done this is where you go. Just be prepared for a lot of Indian terms.

- Charles Stross - The Merchant Princes: A Boston tech reporter one day finds out that she can jump between alternate versions of Earth and that she's part of a large extended family with that talent based in a world at a renaissance level where semi-romanized viking knights control the eastern seaboard of North America and the Chinese have begun colonizing the west coast, and said family is deeply involved in the Drug Trade. That is just the start as events also include a steampunk America ruled by the English crown, homeland security, revolutionaries, dynastic conflicts and more. Good for lovers of crime and intrigue, blending both the medieval and the modern quite well. It also shows a Masquarade in a terminal death spiral, in which a group with fantastic abilities blending in with our society is gradually exposed.

- Harry Turtledove - The Guns of the South: Probably the only Turtledove's book where his massive Confederateboo spazzing is in control. Group of Afrikaaner time-travelers decide to meddle with the American Civil War, chiefly by selling the Confederacy AK-47s and providing General Lee with few bottles of nitroglycerin for his heart condition. Needlessly to say, things go off the rails really fucking fast. Most of the book focus on the post-war situation, following a large selection of historical and made-up characters in this new reality and their interactions with the mysterious "Rivington Men". Being written in 1992, the book is very much rooted in the zeitgeist of then-ongoing political changes in the South Africa, so if you are a zoomer, half of the plot might fly over your head.

- Harry Turtledove - Worldwar series: Lizard-like aliens invade during World War II. To spice things up, they aren't particularly advanced (having roughly late 80s tech) and more importantly they are very conservative, and the whole invasion was based on outdated intel from a probe that reached Earth in 12th century. But since they've encounter the planet in the middle of a global conflict, they decide to land anyway. Follows a bunch of different perspectives from Americans to Brits to Soviets to Germans to Polish Jews to the Lizards themselves, with world diverging more and more from real-life history each month. There's four books in the series, as well as four more books set afterwards that are frankly not worth it. Warning! Since this is Turtledove, expect a fuckload of Wehraboo antics served side by side with an idealistic take on the whole "land of the free, home of the brave".

- Scott Westerfield - Leviathan series: In this absolutely batshit-insane reimagining of World War One, the world is divided into two competing schools of technological thought - the Clankers, who represent machines and mechanization; and the Darwinists, who believe in mutating nature to solve man's problems. Naturally, the Central Powers are the chief adherents of the Clanker philosophy and you can imagine the brutal warfare of the Western Front except with German Steam Tanks versus genetically-enhanced British Abominations. Yeah. Word of warning, the series is advertised as a YA novel series and does feature some questionably mundane character plotlines that do tend to spoil the setting a bit.

Mystery[edit]

- Raymond Chandler - The Big Sleep: The grandfather of noir, single-handedly responsible for establishing about half of all genre conventions and creating the image of what an investigator should be like. If you ever plan to run just about anything about cool detectives doing cool stuff, it's a must read.

- The Lady in the Lake: Probably the most applicable of the books featuring Marlowe, trading the big city and its massive police department for rural nowhere and a much smaller scale investigation, but not stakes.

- Agatha Christie - And Then There Were None: Ten random strangers trapped with a vengeful killer. Or so they think. Aged like milk, but is still one of the staples of the genre and a well-tested premise.

- Harlan Coben - Tell No One: A grieving widower receives a message with a proof that his wife, murdered few years ago, is actually alive and well, and her kidnapping was just a set-up. Like all Coben books, it's a pyramid scheme of backroom deals, conflicting motivations and gaslighting the reader, but due to its plot structure, it's the closest to your near-occult investigation for a game campaign.

- Arthur Conan Doyle - The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: A staple of detective fiction, often to the point of being considered the godfather of the genre. An incredibly useful point of reference for late 19th century social norms and attitudes, on top of being a great influence for mystery-focused campaigns. All of which are short, easy reads. If you run Call of Cthulhu or any period-specific setting relevant to Victorian Britain, Doyle's tales are a must-read.

- Henning Mankell - Wallander series: Swedish crime series, featuring a provincial police investigator Wallander dealing with local crimes in Ystad. It's a blend of your hard-boiled fiction, especially as far as Wallander himself goes, with a very routine, grounded police procedural. As such, it offers just the right level of applicability for modern investigation scenarios, without things getting convoluted, while keeping it modern. Aside the 11 books, both Swedish and British TV series adaptations are approved, too.

Historical Fiction[edit]

- Robert Bolt - The Mission: A journey of a young boy into becoming a murder-hobo and then trying to repent his sins as a missionary, taking place in 1740s Paraguay. But more seriously, it's about the Jesuits and their mission in a patch of land contested between Spain and Portugal, with great, nuanced characters caught up in a conflict they can't even hope to win. Mostly famous for its movie adaptation with de Niro and Irons and cutting the entire backstory which made the book worth reading in the first place.

- Miguel de Cervantes - The Ingenious Nobleman Mister Quixote of La Mancha: The misadventures of an old man driven to madness by reading chivalry novels, being the first major parody of the classic interpretation of that setting. Mixing comedy and a ton of political commentary for its time, it's one of the most important novels of all time, and the elements and tropes it brought to popular culture are referenced and satirized to this day.

- Tom Clancy - The Hunt for Red October: The quintessential techno-thriller, being one of the hallmarks of the entire genre and probably the most famous of all Clancy's book. Tightly written, with plausible story and great characters.

- James Clavell - The Asian Saga: A series of books set in flash-points of historical events in Japan, China and the Malays throughout centuries. For the most part, they are self-contained, so you can pick any of them without fear of continuity. The most famous and recognisable one is "Shogun", telling a slightly fictionalised account of the final years of the Sengoku period, as seen by an English navigator stranded in Japan and slowly learning its customs to survive, while being a plaything in the ongoing power struggle between various daimyō, Portugese and the Catholic Church. If you ever needed tips for "stranger in a strange land" campaign or big political pile-up that pays off, pick any of those books. Mind the page-count.

- Bernard Cornwell - Sharpe: A series of books following Richard Sharp as he rises through the ranks of the British Army during the first few decades of the 1800s (the bulk of it set during the Napoleonic Wars). More commonly known by its great TV series, staring Sean Bean.

- Michael Crichton - Eaters of the Dead: Blending real accounts of Ahmad ibn Fadlan, a 10th century Arabian traveller, and epic of Beowulf, the novel neatly shows how little divides myths from history. But mostly, it's just vikings fighting against cannibalistic neanderthals, in a quest to defeat the evil monsters attacking the locals and fulfilling a prophecy. How badass is that? Its adaptation, "13th Warrior", while diverging from the book significantly, is one of the quintessential /tg/ movies and also approved.

- Alexandre Dumas - The Three Musketeers: It's THE swashbuckling novel. You probably more or less know what is it about just from its sheer impact on culture and pop-culture. Duels, political intrigue, romancing and most importantly, friendship above everything. Has bunch of continuations, along with just as numerous adaptations.

- Paul Féval - Le Bossu [or The Hunchback]: The other swashbuckler. Chevalier Henri Lagardère swears vengeance over the death of his friend, duke de Nevers, while escaping with Nevers' infant daughter Aurore, from the hands of assassins. Years later he returns, in disguise of a hunchbacked accountant, to wreck havoc and have his way with the villainous prince de Gonzague. In the background, France is trying to figure out itself after the death of Louis XIV and the resulting regency. Both film adaptations are approved genre classics.

- C.S. Forester - Horatio Hornblower: A series of books following Horatio Hornblower as he rises through the ranks of the Royal Navy from the late 1700’s through the early 1800’s. Has a TV series adaptation free off YouTube if books aren’t your thing.

- George MacDonald Fraser - Flashman: A 19th century, cowardly and womanizing British buffoon with a pedigree goes from one crazy adventure to another around the globe. Meanwhile the writer has fun with all the genre conventions and relentlessly mocking the Victorian literature. A little on the nose, but how else you turn stuff like Kipling into actual engaging adventuring?

- Homer - The Iliad: One of the oldest pieces of historical fiction. Trojan prince steals a Greek king's wife and all of Greece comes for revenge. For a long time considered complete fiction, but excavations and analysis suggest at least at a concept level Homer's epic is based on real war, even if the details got obscured or lost over hundreds of years of oral tradition.

- Luo Guanzhong - Romance of the Three Kingdoms: Often seen as the Chinese epic, while being easily one of the most over-exposed piece of Far East media in existence, attributed to a guy who merely edited the final version. As the title indicates, it tracks the semi-fictionalised account of the Three Kingdoms period: a civil war over the corpse of the decaying Han empire, where everyone wants a piece for themselves, regardless of their claimed agenda. Thus its an archetypical dog-pile of court intrigues, epic battles, personal struggles and eventual betrayal of your allies and friends - and unlike majority of stuff like this, the dozens of sub-plots do have their pay-off. Said payoff means there is a warning to be given: a proper adaptation of this monstrosity is an 80-episodes long TV series, since traditionally, it's been printed in five, thick tomes.

- John Jakes - the Kent Family Chronicles and the North and South trilogy: Respectively: an epic family drama about American Revolutionary War and an epic family drama about American Civil War, doing back and forth between main characters' personal lives and the frontlines of the wars they are participating or end up dragged into - and then revisiting them in the aftermath of the conflict. Neat historical backdrop for both of the conflicts and avoiding typical Ameritard pathos about their own history, making it digestible even for non-Yanks. Both cycles have been adopted into equally approved TV mini-series.

- Allan Mallinson - Matthew Hervey series: If Captain Aubrey was the pinnacle of Napoleonic naval escapades then the career of Matthew Hervey is the pinnacle of life in the cavalry regiments of the time. A series of 14 splendid novels, the level of detail is tremendous, touching on many of the equestrian and veterinarian aspects of cavalry upkeep and warfare that is presented in a much more manly fashion than what passes for horse-care in those sappy teen's novels. Also helps that the author was a bona-fide military officer of the (Queen Mary's Own) Royal Hussars. If you've ever wondered how the fuck the armies of the 19th century could maintain so much cavalry and how those regiments lived, this is the series for you.

- Cormac McCarthy - Blood Meridian: Set during the middle of the 19th century in the southern United States, it follows the exploits of "The Kid" who joins what is essentially a band of Murderhobos to terrorize the prairie and hunt Indians. It doesn't sound like anything special, until you count in the fact that the group is possibly led by the devil himself. And he leads the group on to ever greater acts of depravity that would make Khorne and Slaneesh uneasy.

- Margaret Mitchell - Gone with the Wind: The original "subverting your expectations" novel. In fact, doing it so hard, the stock plots and characters from ACW romance stories it was subverting (and mocking) are now completely forgotten. A historical romance slash business guide, following adventures of Scarlett O'Hara, a spoiled Southern belle that will stop at nothing to keep her status, even if Sherman's march and Confederate defeat left her destitute and in rags. All while Scarlett is completely oblivious to what sort of awful person she turns into. Warning: the book is thick enough to kill someone with it, while the (approved) adaptation comes with two intermissions.

- Brian Moore - Black Robe: A French Jesuit on his perilous quest to reach a remote mission, helped by distrusting Algonquian guides and crossing with them the bleak, frozen hell that is pre-colonial Ontario. The novel combines two elements that make it worth reading: it is well-researched on all covered subjects, creating a very handy panorama of 17th century Canada, and, more importantly, it puts a nice spin on the generic "travel up-stream through all sort of dangers" plot to make it interesting. The film adaptation is also approved, in many ways being even better than the book.

- Patrick O'Brian - Aubrey–Maturin series: A series of 21 nautical historical novels, set during the Napoleonic Wars and centering on the friendship between Captain Jack Aubrey of the Royal Navy and his ship's surgeon Stephen Maturin. Almost autistically well-researched and amazingly addictive series which should be read by just about anyone even wishing to run a maritime-themed game. They are really addictive, so make sure you have enough time to spare before starting reading. The film adaptation is also approved.

- Erich Maria Remarque - All Quiet on the Western Front: The personal story of a German soldier named Paul Breuer, who details the exploits and sufferings of his regiment during the 1st World War on the Western front. If you are looking for an account of how truly and utterly apocalyptic WW1 was, look no further. The book details almost every part of a soldiers life, from chilling behind the front lines to storming an enemy trench and the author (who himself fought in the war) is at times damn straight and at other times damn poetic about it. Beautiful descriptions of nature and accounts of friends being ripped to shreds by grenades are often just a paragraph apart, so its quite the rollercoaster.

- Since it's a pretty short read, it leaves you with time to indulge in the follow-up, The Road Back, which features the surviving soldiers from the same company (but not the same characters) from the previous book, trying to re-integrate into society and miserably failing.

- Walter Scott - Ivanhoe: The grand-daddy of the entire genre. Adventures and misadventures of a chivalrous knight who does his very best to collect ransom needed for king Richard the Lion Heart, while fending off against those nefarious Normans and their machinations. Despite its age, still holding pretty well.

- Murasaki Shikibu - The Tale of Genji: Arguably the world's first novel, written by a woman no less. It centers around Hikaru Genji, or "Shining Genji" who is the son of an ancient Japanese emperor (known to readers as Emperor Kiritsubo) and a low-ranking concubine called Kiritsubo's Consort. The novel provides great insight into the life of Heian-era Japan. As such, brace yourself for everyone constantly crying and/or getting emotional like bunch of emo kids.

- Neal Stephenson - The Baroque Cycle: Adventures of a really big cast of characters living amidst of the central events of the late 17th and early 18th centuries in Europe, Africa, Asia, and Central America. Extremely well-researched portray of the era, seamlessly blending history with fictional characters. And a real door-stopper.

- Robert Louis Stevenson - Treasure Island: If by any chance or twist of fate you still didn't read it, you damn should right now. Absolute classic and absolute gold mine for ideas, not even for pirate game, but just adventuring in general.

- Mika Waltari - The Egyptian, The Etruscan: "The Egyptian" follows the life of a fictional Egyptian Sinuhe living in the New Kingdom period and witnessing the upheaval that monotheism and war with Hittites bring to the ordered Egypt. "The Etruscan" does the same for Turms, an amnesiac hero set in the time of Greco-Persian Wars and the beginnings of the Roman Republic. Waltari was recognised and lauded by the historians at the time for spending autistic-levels of time researching the cultures he was writing about - but don't expect too much of it still hold value, century of additional research later.

- Kawabata Yasunari - The Master of Go: The story of a brash young power gamer challenging a grizzled old neckbeard to a championship Go match. Chronicles the national-scale edition war that was 1930s Japan through the medium of gaming obsessed hyper-autists.

Weird Stuff[edit]

- Dante Alighieri - The Divine Comedy: In this section because due to genre-spinning hybrid that it is. It is also a very trippy experience. The Divine Comedy is best known for its first part, the Inferno, which pretty much codified culture and pop-culture take on Hell. Beyond that, its also a good look at Renaissance, with both its politics and fascination in antiquity. The second and third parts are much more esoteric and increasingly focused specifically on Christian theology, but worth looking into for Dante's literary skills. Some Italian madlads have even made a Dungeons & Dragons 5th Edition campaign setting out of it: see Inferno for the gory details.

- David Brin - Uplift Hexology: A sort of really lazily worldbuilt sci-fi setting, based around the idea that a trillions-years-old galactic civilization is perpetuated by the "uplifting" of near-sentient animals and tool-using species. Every species has its specific attitude and special trait, like most bad sci-fi, except for humans and their uplifted dolphins and chimpanzees. But it does have some interesting ideas about evolution and how that could lead to truly strange forms of life and ways of thinking, if you can suffer through all the ecofanaticism.

- Daniel Falconer - The World of Kong: A Natural History of Skull Island: Created as a tie-in to the 2005 remake of King Kong by Peter Jackson, this book is a glorified encyclopedia that explores the geography, flora and fauna of Skull Island as depicted in the film, vastly expanding upon the pulp fantasy-influenced artificial environment designed for the film. This book is a goldmine for worldbuilding and creature design if you want to do a Sword & Sorcery or fantasy Stone Age setting, or just include a "Lost World of dinosaurs" type area in your own setting, with an incredible variety of fleshed out beasts ranging from small, inoffensive coastal grazers to apex predators. The only drawback is that it's out of print and extremely hard to find in physical copy at a non-exorbitant price.

- Stephen King: Exactly which King books are worth recommending here is highly open to debate, as he's put out a lot of novels. The Dark Tower books are fairly /tg/ adjacent (to the point they're recommended separately below, mainly due to being non-horror), and the Mr. Mercedes series is a decent model for a "supernatural detective". Note that he has also written a lot of stuff that's either not very good, or only minimally useful for /tg/ purposes (it might give you a neat idea or two to steal, but rest of the book is the sort of plot that will never work as a game). His output under the pen-name Richard Bachman shares the same issues. Adaptations are just as varied: from absolute classics, through applicable to /tg/ despite low quality, to best ignored.

- The Dark Tower: King is normally known primarily for his horror writing, and recommended as such above, and while the Dark Tower does have its horrifying moments, it has much more than that. This book series is part Western, part Adventure, part Sci-Fi, part Fantasy, etc. The premise is that the last living Gunslinger, Roland Deschain, must reach the Dark Tower and prevent its collapse, or else all of reality will fall with it. With his friends plucked from different points in history to fight at his side, they face off against a gamut of bizarre enemies, including an evil wizard, various demons, a homicidal train AI, and even Dr. Doom robot furries armed with lightsabers and explosive golden snitches (no that is not an exaggeration, that is a very literal description). Even King himself appears in the book series, with his real life car accident being an important plot point. The story’s dimension-hopping premise makes for a good TTRPG - which is why The Dark Tower RPG exists.

Mythology[edit]

- Beowulf: Beowulf, the questing adventurer, rips off an arm of monstrous Grendel, then goes down into a lake to kill Grendel's mum after she offs his friend. Beowulf becomes a king and is eventually killed by a dragon, but makes his friend his successor before dying. Be warned: while it sounds like the manliest adventure ever, in reality it's incredibly dull to read.

- The Epic of Gilgamesh: The original Conan, gettin' bitches and slayin' witches since 1800BC, baby. The story of Gilgamesh (no shit; might have been Bilgamesh originally), a demi-god Sumerian king who the gods continually try to beat down and/or kill because he's just that fucking awesome. He's also a HUUUUUUGE dick. Eventually meets his best bro for life Enkidu and they go on fuckin' sick adventures. Unfortunately some parts of the story are lost.

- Journey to the West: One of China's most famous bits of literature, which covers a broad range of topics including Chinese myths, monsters, folk tales, and Buddhist thought in general. Best known on /tg/ for spawning everyone's favorite anime/manga about a certain half-monkey xeno super fighter and its main character featuring in a load of fantasy games, including D&D and Warhammer Fantasy, and just about every known MOBA/"Aeon of Strife Styled Fortress Assault Game Going On Two Sides". Preferably find an abridged version below 400 pages, for the whole thing takes an entire bookshelf and is written in a sickeningly repetitive style of a Buddhist parable.

- Kullervo: Some Finnish nationalist figured, how come we don'ts gots a mythology. So he made one - the Kalevala - but with even MORE grimdark and incest. JRR Tolkien edited a rendition of the Kullervo subset and, further, both he and Moorcock independently(?) took inspiration for their own antiheroes with magic souldraining swords, Turin and Elric respectively.

- Mahābhārata: A Hindu epic story about family struggle for the rightful rule, performing your religious duty and also... pfft! Just kidding: it's wall to wall tits, ultra-violence and bullshit superpowers. But also family struggle, romances, political intrigues and handy panorama of nascent Hindu religion. Also - magnificent mustaches, the manlier you are, the bigger the stach. It's THE ultimate Bronze Age epic, long enough to take an entire bookshelf by itself. As such, you should be looking for an abridged version around 600-800 pages, rather than the whole thing.

- Der Nibelunge liet (The Lay of the Nibelungs): A ring is found at the Rhine; a dragon (Fafnir, for Wagner) finds it; dragon gets BTFOed by one Siegfried who is then corrupted himself. Written around AD 1200 by a High German, that is high up in Bavaria; with many parallels to similar stories in the Edda far north. Deemed too pagan for the Renaissance-era Germans, lost in the ensuing religious wars; rediscovered 1755 and became the national epic... for better or worse. Wagner's /pol/-approved take (Fafnir is a greedy dwarf, becomes that dragon) pulls more from the Norse. That's the one wherein wabbits are killed.

- The Odyssey: Sequel to Homer's Iliad, possibly by a fan adopting that name. Odysseus, hero of the Trojan War with many cameos in the Iliad, has to go home to his wife - but he's in no hurry. Runs through many adventures before finally getting there; his wife somehow had stayed more loyal than he had. Many C.S. Lewis and then D&D monsters got aired here first. [Also] in Iliad / Odyssey fanfic may be included the Cypria and the Aeneid; Argonautica, concerning Jason's earlier voyage to the Black Sea, further had much influence from this book.

- The Poetic Edda: A historical source, the Poetic Edda provides most of the basis for what we know about Norse myth and belief today. The mere fact that it's Viking myth poetry written in Old Norse should entice most fa/tg/uys, but for those somehow unmoved still, it's basically THE sourcebook for the Lord of the Rings and all else Tolkien. If you want to know where Gandalf (who is basically Odin), Dwarves (and their names), Elves, the phrase "Middle Earth" and that obsession he has for massive trees came from, then look no further. Also, pick up a copy of the Prose Edda while your reading this one, seeing as you're on a roll. Features a now-confirmed-to-AD-1022 visit to Newfoundland ("Markland"), whence the Norse bugged out in a generation because who the fuck wants to spend more time in Noof than one has to.

History & Non-Fiction[edit]

- Julius Caesar - Commentaries on the Gallic War: If you study Latin, this is the first full text you'll be assigned to translate (same goes for Xenophon if you're learning Greek). Caesar wrote this autobiography of his campaign in Gaul to bolster his support among the only so-so literate plebs, and as a result it avoids using big, confusing words. On the flip-side, this makes it dreadfully dry and boring at times. Still, if you want to have the Roman experience, it's a mandatory read.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero - De Re Publica: A political dialogue, explaining all the virtues of Roman Republic. Survived only partially and in short-hands, but still makes a compelling read about "ideal" (and most definitely not idealised into absurdity) state of Roman politics and political machine, along with all the machinations gradually leading to the Republic turning into the Empire. An obligatory read for all Romanboos.

- Herodotus - Histories: As a historical account, it's almost completely useless and predominately fictional, being single-handedly responsible for bunch of deeply ingrained popular misconceptions about ancient Persia, Egypt, Sparta and Scythia. What it really is is the ancient world's equivalent of a gossip column, thus collecting all the most interesting, crazy and outlandish stories Herodotus heard or copied from others. As such, it's a perfect base for equally outlandish world-building and campaigns, mixing reality with fantasy.

- Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli - The Prince: This guy seems to be very underrated in popular culture, and its name is often used as a pejorative term, sometimes as twisted or evil. But this guy only wrote some sort of historical summary of how previous governments around the world have risen to power, how they handled it, and how they lost it all. It's just a guide of how you should rule your kingdom. You totally won't find Skub here. There is a later version of the book with additional commentary by Napoléon Bonaparte, which is naturally the preferred version. A major influence on Camarilla of Vampire: The Masquerade (note the name of their leaders).

- Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith - The Dictator's Handbook: Similar to the previous work, this book goes over Selectorate Theory and it's historical examples across time as to how Politics and power works across various societies. Although this page isn't for the political implications of the theory, it can be useful for creating a setting or campaign, especially if the BBEG needs a rationale for his actions, or if you want to understand the behaviors of the Imperium's inefficient and horrible bureaucracy. Potentially also could be used to explain the ever skubtastic Bretonnian lore about how aristocrats act and whether or not its realistic to expect.

- Gerard K. O'Neill - The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space: THE sourcebook if you're going to run hard space sci-fi. A terribly dry, scientific thing that explains in headshrinking detail how to build cities in space. Popularized the "Island" series of space colony designs that Gundam and Babylon 5 copied from. While written as a popular science, it is nowdays technically a sci-fi book, since it extrapolates the Apollo program well beyond anything that was or even is feasible nowdays on practical level.

- Jan Chryzostom Pasek - Diaries (Also known in English as The Writings of Jan Chryzostom Pasek, a Squire of the Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania): Diaries (duh) of a 17th century nobleman, who, due to spending his life fighting in countless wars and even more quarrels with his neighbuors, traveled half the Europe and always had something to say about the things and people he saw. If you are yearning for your pike-and-shot, but also need some cavalryman crazy panache, look no further. Due to its writing style, it reads almost like an adventure novel and, as improbable as it seems at times, actually happened for real.

- Antonio Pigafetta - Journal of Magellan's Voyage: A historical account of the first circumnavigation of the globe. Aside obvious historical value, it's worth to note Pigafetta wasn't an explorer himself or a member of the crew - he was a tourist, joining the expedition for the thrill of adventure and described everything from such perspective. Provides a lot of nautical and ethnographical observations, creating a panorama for Age of Discovery.

- Marco Polo - The Million: The seminal travelogue of an Italian explorer as he travelled the breadth of Middle East and Asia all the way to China and back again during the height of the Middle Ages. While there is some question as to the accuracy of the work, scholars today agree that generally speaking the accounts are as accurate as can be expected for the time period.

- Sun Tzu - The Art of War: The Codex Astartes of ancient China dating back to the Spring and Autumn period. Essentially a "How to Wage Wars for Dummies" guidebook and, as such, somewhat trivial from a modern perspective - which doesn't stop people from gushing how brilliant it is and making it one of the most mis-quoted books in human literature (partly because it was designed to be quoted, as Sun Tzu was writing in a time when literacy wasn't that common in the first place). Most editions contain more commentaries than there is actual Sun Tzu writing in them.

- Publius Cornelius Tacitus - The Annals: A Roman historical account of the time from Augustus' death in 14 AD. to the reign of Emperor Nero. Although fragmented as hell (as the overwhelming majority of ancient literature is), it is one of the most important sources on how the Roman Empire survived and gained permanency after its charismatic founder Octavian-Augustus died. It is generally regarded as being one of the finest works of Roman history that has survived, as well as containing one of the only extra-biblical accounts of Jesus, alongside the writings of Flavius Josephus. Tacitus is especially appreciated for his penetrating insights into power politics, so think of him as a proto-Machiavelli in far more readable prose.

- Thucydides - History of the Peloponnesian War: Happens right before The Anabasis, covering roughly two decades of warfare between Athens and Sparta, in varying degrees of detail depending on the sources Thucydides had access to at the time (he was exiled from Athens and switched sides mid-war). Trails off at the end, presumably he died writing it. Basically the oldest human text in existence that is regarded as a historical account to be taken at face value, and it inspired many other leaders such as Xenophon and later Julius Caesar to write accounts of their own deeds.

- Xenophon - The Anabasis: Another historical account, this time of the journey of 10,000 Greek mercenaries (hence the other title - The March of the Ten Thousand) who end up stranded in the middle of Persian Empire after their employer, Cyrus the Younger, got killed in the battle. Problem is, Cyrus was trying to overthrown his brother, king Artaxerxes II, using said Greeks. So now they are in the middle of hostile territory, with no means to resupply, no support and constantly endangered by Persian military and tributary locals. Due to Xenophon's writing style, the book is highly entertaining and action-packed, while also providing countless descriptions of both Greek and Persian customs. And if you wonder why the plot sounds familiar - you probably saw "The Warriors".

Shunned/Hated[edit]

- Terry

GoodBadkind - The Sword of Truth: An infamous series full of Terry's magical realm BDSM, utterly gratuitous rape and torture (Terry's cheap/lazy method of making his main characters look better by comparison), and "heroes" we're supposed to arbitrarily like no matter what horrible things they do. Badkind himself having nothing but contempt for the entire fantasy genre while bragging about how he was a "serious" novelist and packing the later books with his stupid Ayn Ranting (even when it contradicted previous fucking events) did him no favours.

- Stephenie Meyer - Twilight: ...Have you been on the internet? The series that single-handedly killed an entire style of modern fantasy vampire for an entire generation of fantasy fans who aren't sexually-frustrated housewives and/or hormone-addled teenage girls. Though it's a bit old hat to bring up the series with any seriousness, doing so will irritate the scars of bitter neckbeards. (Hey, at least it's less terrible than "Fifty Shades of Grey", which is worse in just about every measure.)

- John Norman - Gor: A cheap knockoff of Barsoom and Conan made notable (as the series goes on) for having a lot of half baked philosophizing, skeevy BSDM stuff and a ton of fucked up ideas about gender, slavery and sex. In brief a bunch of bug aliens make a zoo full of humans to live "as nature intended" as misogynistic slaving barbarians and make sure of it by incinerating anyone who attempts to develop technology or societies they don't approve of with laser beams. Which they sometimes do to whole cities just for the lulz. Also for spawning one of the original obnoxious apologist Internet subcultures, the Goreans. Spread to Second Life, so go there if you want to burn your brain.

- Christopher Paolini - The Inheritance Series: A Mary Sue main character, his dragon and a derivative plot. It was written when Paolini was a teenager and it shows. Every single book could stand to lose at least a third of its wordcount and there are lot of times when the plot grinds to a halt for entire chapters just for the characters to think and ramble about the inanest topics. Less offensive than other stuff on this list since it lacks traits such as bootlicking fans and an asshole-ish or agenda-driven author. The author also put a decent amount of effort into his worldbuilding and actually attempted to address legitimate criticism, which is more than can be said for Badkind, GNorman and Smeyer. If you must, start in book two and read his cousin's story, he is a farm boy turned blacksmith who was getting his dick wet while struggling with a hostile father-in-law, until the civil war reached his hometown and his betrothed is whisked away by humanoid bug-birds, he then murders 200 people with a hammer and deals with PTSD.

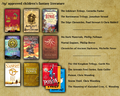

Gallery[edit]

-

Kid-tested, fa/tg/uy-approved.

-

The Dune reading guide